Fishing for Origins: The Curious History of Kerala’s “Chinese” Lift Nets

- archivesofthesea

- Jan 18

- 15 min read

By Roxani Margariti.

Dimitra’s fascinating examination of the majestic species Thunnus thynnus, its cousins, and the lethal traps that brought them to markets through the ages rekindled my curiosity about the spectacular stationary fishing nets I saw in the South Indian state of Kerala during a visit there in the summer of 2024. Lining the shores of the city of Kochi, historic Cochin, the nets and their cantilever frames feature in countless photographs that capture their silhouettes against dawns, sunsets, and the waters surrounding this storied port. They have become emblematic of the place and its history.

The so-called “Chinese Nets” or cheenavalla as these are known in Malayalam, the language of Kerala, are locally considered monuments and protected cultural heritage. They feature in promotional material for the city’s thriving tourism industry, and tourist guides offer introductions and even hands-on experiences at the nets to eager visitors. They have even been immortalized in a 1970s film—and even if you don’t know Malayalam, it is well worth watching for its stunning takes of waterscapes, watercraft, fisherfolk lives and instructive images of the nets!

How all this fame and symbolism translates into the nets’ upkeep is not entirely clear, however. This past November, a tour guide inadvisably led a group of tourists to climb the wooden platform that forms part of the net’s cantilever structure and that proved to be in disrepair: the rickety platform gave way under the weight of the visitors who ended up in the water! (fortunately there were no serious injuries). The accident shed light on the nets, the difficulty of preserving them, and the disconnect between the rush of tourism and modern industry, the logistics of historic preservation, and the needs of the local fishermen, who continue to use them.

So, what of the actual fishing with the Cheenavala—and why are they traditionally thought to be Chinese? How are they built, how are they operated and maintained, what catch do they land, and how big of a yield do they provide? In this post, we will explore the nature and curious history of Kerala’s most well-known stationary fishing nets. And we will contemplate the ways in which technologies both travel and parallel each other across the world—the local use of a particular technology potentially telling both a very rooted and a very connected story!

Cochin, a city of waterways

Το tell the story of the Cheenavalla nets, I first need to say a few words about the port city of Cochin, modern-day Kochi, and its charismatic geographical location and topography. In sum, Kochi is a city of waterways! The modern city lies astride a complex estuary between the Laccadive Sea (the southeasternmost section of the Arabian Sea) and the region’s so-called “backwaters.” Backwaters are a remarkable web of interconnected inland lagoons and river estuaries that stretch for about 200 km parallel to the coast, issuing into the ocean near Cochin and constituting one of Kerala’s most characteristic geographical features.

Backwaters, rivers, and the sea thread through Cochin. As a first-time visitor making my way from Kochi’s sparkling brand-new airport, some 40km northeast of the city proper, to the historic center at Fort Cochin, I found it somewhat hard to orient myself as we criss-crossed several strands of brackish and salty water and chunks of dry land.

The Keralan Backwaters are a fascinating aquatic world in and of themselves, complete with specialized watercraft—tourist house boats, racing “snakeboats,” and amazing vestiges of the Indian Ocean’s sewn boat tradition—fishing installations using a variety of gear, and ways of life that I cannot fully do justice to here—a great topic for a future post perhaps! For the story of the Chinese nets, suffice it to say that these stationary fishing devices crop up along inland, backwater shores just as they do on Cochin’s seafront.

The early history of the Cochin before the 15th century is somewhat unclear. What is certain is that it was shaped by both its topography and its location in the historical region of Malabar, which more or less coincides with modern-day Kerala. The region’s early contacts with the world beyond its shores revolved around the trade in its most famous product: black pepper. In Cochin’s immediate vicinity stood two important entrepots trading in pepper and other spices in the ancient and medieval period of Indian Ocean trade respectively. The earliest of these was Muziris, a center of trade mentioned in the 1st-century Greek traders’ manual Periplus of the Erythraean Sea and most likely to be identified with the site at modern-day Pattanam some 15 km from old Cochin.

After Muziris came Kudungallur, site of a renowned early mosque located some 30 km north of Cochin (possibly to be identified with the town of Shingly of medieval Jewish sources). In the late medieval period, starting sometime in the 14th century, Cochin took over as the main entrepot of this area. Shortly thereafter, in the early 15th century it was visited by the Chinese admiral Zheng He and it is to this period that the Chinese nets are said to originate. We shall see below why. But let’s first look at the nets themselves!

Dip and lift: structure and operation of Kerala’s stationary nets

The cheenavalla are stationary fishing gear, like the thyneia that Dimitra so vividly described. But unlike the thyneia, the Keralan Chinese nets are “dipnets” or, as fishing-gear expert Adres von Brandt explains, what is more correctly described as “lift nets.” These nets are suspended from poles fixed to a base, baited, lowered onto the seabed, then lifted with the catch. Sometimes lamps are placed near the nets to attract fish. Several basic fishing gear and techniques are combined in the function of this tool.

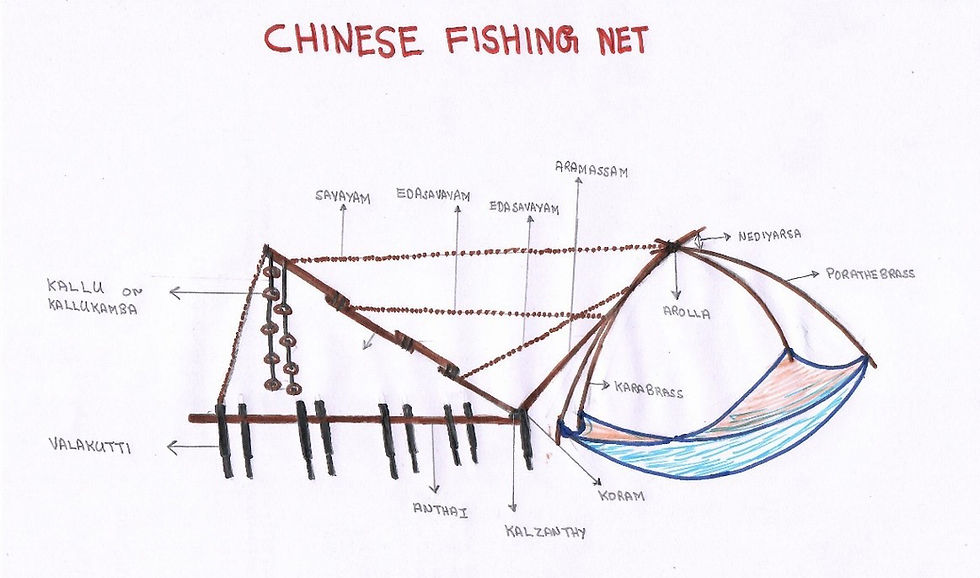

The structure onto which the nets are fixed was—and is some cases still is—made of wood (teak is often mentioned) but nowadays metal elements have been introduced in many cases. A set of horizontal beams or planks and vertical stanchions make up a base platform. Fixed at the water end of this platform with joints and ropes is a set of cantilever beams. From the forward (waterside) beam hangs a four-pole frame onto which sheets or blankets of nets are tied. The lowering and lifting works by pivoting the cantilever component, sometimes employing the weight of a person walking out on the forward beam, while the back beam is weighted with suspended stone weights.

The operation of the nets begins with lowering them horizontally, either to mid-water or all the way onto the seabed. They are left there for a period of time with the expectation that fish or crustaceans will swim or crawl on them; and are then lifted to land the catch. This process takes place after sundown and continues through the night till the early hours of the morning. Sometimes fishermen use lamps to attract fish, though the use of lamps is prohibited by state regulations in some cases. The catch varies, but two of the region’s most sought-after species for the gourmet table are said to be caught with Chinese nets: Chemmeen (a common term for prawns, of which Kerala has several species) and Karimeen (the Keralan common name for the pearlspot, scientifically known as Etroplus suratensis). A hefty report about fisheries and other economic activities at Cochin’s estuary published by Cochin University’s K.T. Thomson shows that for the year 2001-2002, catch landings from Chinese nets were eight percent of the total landings of all types of gear, yet accounted for fifteen percent of total value of fish sold.

KT Thomson also notes that the size of the gear varies, and depends on location and the prevailing conditions: depth of water, strength of currents, availability of labor. Larger gear is used along the outer shores of the estuaries, where the sea meets inland waters and currents are stronger; these structures require more workers to operate, six or seven at a time. It is these nets that one sees around Fort Cochin, the Kochi’s historic district. But Kochi is situated between sea and Kerala’s inland waters (known as backwaters, as we saw above) and Chinese nets are also found along those inland shores of the Cochin estuary. There, on these more placid waters, fishermen set up smaller gear, which two or three men can operate.

Placement and operation have many economic and social implications. Customary practices of the fishermen have included self-regulation and the artisanal nature of the production has ensured some level sustainability. State regulation has been attempted since British colonial days but has been heavy-handed and not easily enforceable.

Modernization and the Cochin Port Authority’s priorities include international trade and industrialization. Dredging of waterways to make space for large commercial vessels and licensing of industries that are located along the shores and are dumping waste into the surrounding waters, are developments that have degraded the environment and squeezed fishermen and net operators. The logistics and politics of where and how the nets are operated is a complex matter and an on-going story. We cannot do justice to it here, but please check out some of our references to studies by Kerala fisheries specialists!

Cochin, China, and the Chinese Nets

The common story about the origin of the Chinese nets is…that they came from China! Standardly, it is thought that the Ming admiral Zheng He brought them to the city as a gift from the Chinese emperor or that the visit and the contacts the Ming expeditions of the 15th century initiated between India and China resulted in the transfer of the technology—see for example a good rendition of this story on the webpage of the Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry. A related notion is that Chinese sailors, who came on Chinese junks, a ship type much larger than its contemporaries around the world and not unlike a floating city, brought the nets with them on these Chinese voyages to Malabar.

In his standard reference work Fishing Methods of the World, Andres Von Brandt notes that the Kerala dip/lift nets are known as “Chinese nets” and explains that similar gear is common across East Asia. But then he also suggests that they were introduced to Kerala by the Portuguese. Does that mean that the Portuguese got them from their attempted colonies in Macau or Southeast Asia and brought them to Malabar? If so, why don’t such lift nets exist further north, on the coasts of Karnataka and Gujarat, closer to the center of gravity of the Estado da India—the Portuguese colonial state in Asia—and its capital port city of Goa? It is important to note that other areas of the world have similar contractions, including places as far apart as Thailand and Italy! Were these nets used in Portugal in the past? They are certainly not in use today. Nowhere else do these nets seem to be called Chinese nets. Why so in Kerala?

The Chinese connection begins in the 14th century and Cochin’s rival city Calicut (present-day Kozhikode). When Ibn Battuta—by now a friendly face on our blog—made his way down the western coast of India and visited Malabar in the 1330s, Calicut was flourishing. In Calicut, or rather at one of its ports, he encountered Chinese vessels (junks), which he describes in vivid detail. Although he mentions life on board the junks, including the fact that the sailors brought their families along and grew vegetables on board, he never mentions fishing or Chinese nets. Nor does he seem aware of the existence of the city of Cochin and it is unclear whether Cochin was of any significance in his day.

But less than a century after Ibn Battuta’s visit, Cochin was certainly an important place. It appears in texts describing the westbound voyages of Ming dynasty envoys Yin Qing (early 1400s) and, most prominently, the eunuch admiral Zheng He (1405–1433). The Chinese texts resulting from these expeditions suggest that Calicut and Cochin had become rival kingdoms sometime between the 14th and the 15th century, and indeed the ruler of Calicut eventually occupied Cochin in the latter part of the 15th century. Interested in expanding their state’s influence in the Indian Ocean, the Chinese delegates of the Ming state brought diplomatic gifts and perhaps played on the rivalry between the two cities. Among these gifts that the admiral Zheng He is said to have given the ruler of Cochin was a monument known as the Cochin Tablet. Its inscription, conveying a Chinese-centered version of the encounters, asserts that the people of Cochin celebrated the debt of the city and kingdom to the Ming emperor and Chinese sages thus:

How fortunate we are that the teachings of the sages of China have benefited us. For several years now, we have had abundant harvests in our country and our people have had houses to live in, have had the bounty of the sea to eat their fill of, and have had fabrics enough for their clothing. Our old are kind to the young, and our juniors respectful to their seniors; all lead happy lives in harmony, without the habits of oppression and contention for dominance. The mountains lack ferocious beasts, the streams are free of noxious fish, the seas yield rare and precious things, the forests produce good wood, and all things flourish in abundance, more than double what is the norm. (Translation as quoted in Louise Levathes, When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405–1433, pp. 216–218)

Notice here the reference to the “teachings of the sages of China” and their effect on “abundant harvests,” including the “bounty of the sea” feeding the Cochin denizens, the indirect nod to fishing in streams, and the explicit mention of “rare and precious things” yielded by the sea. Should we read these words as signaling that their authors had in mind a technological transfer of stationary nets from their Chinese homeland to Kerala? Such assumption would have to remain vague and inconclusive at best! In sum, Ming texts provide no explicit evidence that such fishing technology was indeed among the diplomatic gifts or ordinary technological loans brought to the western Indian shores by the Ming fleets and sailors.

The drama of the power struggle between Calicut and Cochin continued in the 16th century, when the arrival in the Indian Ocean of Portuguese, Ottomans, and eventually the various European East India Companies sought to infiltrate the existing markets and transregional networks. The Portuguese famously antagonized the rulers of Calicut partly by striking alliances with their rivals, the rulers of Cochin in the 1500s. In the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company followed on the footsteps of the Portuguese Estado da India a little too closely and ended up ousting them from some of their hard-gained footholds around the Indian Ocean—including from Cochin and the rest of Malabar in the 1660s.

None of this was a one-sided, European game: both the Portuguese and the Dutch relied on local rulers of Cochin to gain access to the local networks. The exchanges were substantial and pertained to ideas but also craft practices. A palace for Cochin ruler Vira Kerala Varma was originally built in the 1550s by the Portuguese “to pacify him and to compensate for having plundered a temple in the vicinity.” Located in the district of Mattencherry, this structure was then enlarged during the Dutch take-over into the impressive edifice, known today as the Dutch Palace or the Mattenchery Palace and featuring a fascinating mix of Keralan and European architecture. Also fascinating is its interior decoration with a series of stunning murals illustrating the dependence on local craftsmen.

As far as I have been able to establish, the so-called Chinese nets do not appear in such records of the period and no concrete connection exists between the introduction of this technology and the presence in the region of the Portuguese or the Dutch. But in the stunning murals of the Mattenchery palace, there is an elusive, yet tantalizing hint. The murals depict the story of the Ramayana, the great Indian epic centered around the abduction of god Rama’s wife Sita, as well as scenes from the life of the god Krishna. They are usually appreciated for the vividness and even uniqueness of their rendition of these important religious classics. But among the vividly colorful details of these beautiful murals, what stuck out to me during my visit were the images of sea-creatures bordering some of the well-known narrative scenes. These border freezes show fishes, crustaceans, a ray, even a crocodile (perhaps the Keralan native Crocodylus Palustris!) as well as a fantastic mermaid-like creature. The arrangement of these figures on the bottom border of the painting is such that it recalls the bottom of the sea, or river, or lagoon—the artists perhaps conveying an understanding and knowledge of the very undersea where the Chinese nets were lowered!

Ultimately, the origin of Kerala’s lift nets is not an easy riddle to crack—and in a land that has consistently seen so much contact with the outside world, east and west, north and south, it is not surprising that outsiders and perhaps insiders too are eager to connect these emblematic and visually striking pieces of technology to those very contacts and cosmopolitanism!

Would you like to know more? We have suggestions!

2 Comments