Built from the Sea: Marine Building Materials and Indian Ocean Cultures

- archivesofthesea

- Aug 13, 2025

- 20 min read

By Roxani Margariti.

Our previous posts have discussed a wild variety of products that humans derive from the sea. But in addition to food, medicine, implements of various kinds, fabrics, and adornments, the sea has provided humans with substitutes for brick and mortar, for stone and timber! Alternative building materials find their way from the sea to dry land, blurring the boundary between the two realms.

Coastal people, the world over and across time to our days, have marveled at the washed out bodies of impressive marine creatures, most notably whales. They have preserved and displayed their skeletons, and have sometimes used their bones in various structures on terra firma.

Moreover, builders on the world’s sea coasts have used timber flotsam to make new things; shipwrecked planks and parts of boats that washed up on shores or disintegrated on beaches have found their way in buildings on land.

Although not of marine origin strictly speaking, these wooden fragments too become part of architectural styles and building techniques that are distinctly maritime and exemplify the continuum between land and sea. On the other hand, also used in construction especially of littoral places is the timber of mangrove, the salt-loving species of tree whose roots thrive in sheltered tropical and subtropical shallows.

Finally, blocks hewn out of live and fossilized coral make up entire buildings and even cities on the shore. Coral towns of the Western Indian Ocean offer a dramatic example of this kind of architecture.

This post explores how all these materials offered up by the sea have made their way in the architecture and built environment of port towns and coastal settlements in the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea and the Western Indian Ocean more broadly speaking. We will focus particularly on pre-modern and early modern times, from antiquity through the middle ages to the 16th century. But, as always, both Dimitra and I are interested in the diachronic aspect as well!

Eating fish and building with fishbones? Tales of the Ichthyophagoi

Ancient authors personify the blurring of land and sea in their description of the Ichthyophagoi, whom we have encountered before on our blog (along with their neighbors the Chelophagoi!). The “nation of the fisheaters” (των ιχθυοφάγων το έθνος) is a broad designation used by Agatharchides of Cnidus (2nd century BCE), Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE), Strabo (1st century BCE-1st century CE) and Arrian (1st-2nd century CE) to describe people living along the shores of the Western Indian Ocean. Their “primitive” nature in the eyes of Greek and Roman authors was in full display in their dietary habits; hence the exonym they were given focusing on a diet that was purportedly exclusive of anything but fish. They were also portrayed as using fish and the sea in profoundly uncivilized ways. The biased view of the reporters regarding the Ichthyophagoi was dim: although eating exclusively from the sea, they are portrayed as not smart enough to have advanced fishing technology. Instead, the ancient authors claim that they collected fish rather than actively fishing for them. Given the clear ideological charge of these descriptions, and the authors’ drive to define these “exotic” populations as radically different from their own “civilized” selves, we cannot put too much stock in the value judgments of fishing methods and the like. Besides, there are elements of the reports that regardless of the authors’ goals and biases, reveal interesting cultural features of the people intended. In addition to eating mostly fish, the Ichthyfagoi are said to also built their dwellings from the sea, specifically with fishbones! Diodorus Siculus, for example, tells us that the Ichthyophagoi who cannot find caves to dwell in, collect the ribs of great whales that the sea washes out, lean them against each other with the curved side outward, and weave seaweed through them (see original Greek here). Is it possible to cross-reference such assertions and arrive at a kernel of truth?

Another classic and rather detailed description of the practices of the Ichthyophagoi appears in the work by Arrian known as the Indica. In the Indica, Arrian transmits the first-hand accounts of the maritime adventure of Nearchus. As the naval commander of Alexander of Macedon’s Indian campaign, Nearchus led what was originally a river fleet along the coast of Baluchistan and Iran to the Persian/Arabian Gulf. Of the Ichthyophagoi in this region he says that,

“The most fortunate (richest) among them build their houses out of the big fish that the sea expels. They pick their bones and use them instead of timber and used wider bones as doors. Among the multitudes and the poorest among them, their habitations are made with the spines of smaller fish.”

Arrian, Ινδική, 29.16. (see here for the original Greek)

If we believe Arrian’s report, the Ichthyophagoi in this area (Gedrosia in the ancient texts) had differential, socially-determined access to what the sea provided in terms of fishy building materials. Although surely exaggerated, more fantasy than fact, this report does convey the notion that the Ichthyophagoi lived in stratified societies. Moreover, using substantial fragments of cetaceans to build structures of all kinds is attested across cultures; any parallels that come to mind please share!

Our example comes from more than a millennium after the Graeco-Roman world’s descriptions of the Indian Ocean Ichthyophagi. The intrepid traveler from the Muslim West Ibn Battuta marvels at an unusual sight in the port city of Hormuz, on the island situated across the homonymous straits:

“I saw a marvelous thing there by the gate of the congregational mosque. Between the mosque and the market was the skull of a fish as big as a hill, with eyes as big as doors. You could see people going in through one eye and coming out the other.”

Ibn Battuta, Travels (for Arabic text see p. 164 here)

The port city on Hormuz island became the center of an independent kingdom that controlled the straits at the entrance of the Persian Gulf from the 14th to the 16th century until it fell under Portuguese control. Both images here come from this later period and depict the port in a rather fantastical Europeanized form. The top image is in a famous collection of city views, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Cities of the World), created by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg and published in Germany in the 16th-17th century, three centuries after the visit of Ibn Battuta. The bottom image, a similarly stylized but more detailed image accompanying an 18th-century German travel narrative, shows a fishing fleet in the lower left corner. Both images from the historic cities website run by Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Jewish National and University Library.

It is hard to be sure but Ibn Battuta is presumably writing about a whale skull that was placed at a prominent spot between the port city’s two hubs, the main mosque and the market. Incidentally, Ibn Battuta also tells us that the food of the people of Hormuz was “fish and dates.” This echoes the stories about the Ichthyophagoi and the emphasis on the fish-eating habits of the inhabitants of southern seas but without the clearly negative judgment of the classical Mediterranean sources. We have neither physical remains nor an image of this fishy arch of Hormuz, but if we take a look at a whale skeleton, such as that of the blue whale named Hope at London’s Natural History Museum, we can surely visualize the effect Ibn Battuta conveys.

In another revealing parallel, the whalebone arch at Whitby in north Yorkshire was built in the mid-19th century as a memorial to the local fishing industry and may give us a sense of why medieval Hormuz might similarly have chosen to highlight whale bones--in the Whitby case clearly a mandible--in the construction of the city gate.

Wreck and recycle: building with boat remains

The standard biography of the prophet Muhammad, known in English as the Life of the Apostle of God, is not known for its maritime stories. But fascinating tidbits do crop up here and there showing the maritime background of the tribes of the Hijaz, which after all lived along Arabia’s western edge and the Red Sea’s eastern coast. It was in this region that the prophet of Islam preached his divine message. A small detail in the story of the rebuilding of the Kaaba, Islam’s central shrine in Mecca, caught my eye.

It happened before Muhammad’s prophetic mission began, and the story goes like this: The Ka`ba, a cubic structure in the middle of Mecca, had been built in time immemorial by Abraham and his son Ismail as the shrine to the One God. According to Islamic tradition, the Meccans later forgot its original monotheistic nature and at the time of Muhammad’s life were worshipping various deities at the shrine. Being a center of worship and a major revenue maker for the city, the Kaaba had nonetheless fallen into disrepair and was pray to looting. The Meccans decided to repair it, and a major part of the repairs involved giving the structure a wooden roof. That became possible when a ship “belonging to a Greek merchant had been cast ashore at Judda (Jeddah) and become a total wreck. They (the Meccans) took its timbers and got them ready to roof the Ka’ba.” The rest of the story focuses on the process of the repairs in which the sacredness of the building had to be respected, and on Muhammad’s role as a go-between when disputes arose among the tribal leaders about who would have the honor to complete the repairs. Minor in the context of the narrative, the detail about the source of the Ka’ba wooden roofing reveals a practice of recycling of shipwreck planks that would have made sense in a land that was almost devoid of timber.

I wouldn’t linger on this detail were it not for other textual and, more importantly, material evidence of this recycling practice. A 12th-century legal deposition preserved in the medieval Jewish repository known as the Cairo Geniza details the fate of shipwrecked estates belonging to merchants sailing from Yemen to India. The witnesses called to testify with regard to the fate of wrecked vessels along the southern coast of Arabia speak of timbers washed up on the shores; they even suggest that these can be recognized as belonging to particular ships. While not directly describing the practice of putting such flotsam to secondary use, it is clear that coastal people were looking out for and collecting planks and other parts of wooden ships that washed up on the arid shores of Arabia. It stands to reason that such material would have been put to good secondary use.

More definitively, we also have examples of ship timbers embedded into walls of buildings in South Arabia! Scholars have pointed out these timbers at the medieval sites of al-Balid and Qalhat in Oman and have examined the holes and grooves in them that constitute characteristics of sewn boat construction. They have used them primarily to analyze this particular boat building tradition in the region. As maritime archaeologist Alessandro Ghidoni avers in his recent book on the subject, the question of the secondary use of these timbers still merits its own study.

Actual marine timber also plays a role in land-based building construction, however! What I call marine timber is the wood of mangrove, a term that describes several species of remarkable, salt-resistant trees growing in the sheltered waters and intertidal areas of the tropical and subtropical global south (though some species exist further north, as well).

The earliest mentions of mangrove appear in Hellenistic and Roman sources describing the Red Sea—and in some cases explicitly associating them with the lands of the Ichthyofagoi! Pierre Schneider has tabulated the somewhat confusing evidence provided by different ancient Mediterranean authors about mangrove. Based on his work, we note that in these sources mangrove is often described as olive trees or bay trees, due to the elongated shape of their leaves and the small round fruit that some of them bear. Clearly, these authors were grasping for analogies with things they knew from their Mediterranean context. The philosopher Theophrastus (4th-3rd century BCE), whose musings and confusion about corals we encountered in our first post on those ambiguous creatures, mentions a variety of plants that grow in sea water in various regions of the western Indian Ocean in his botanical treatise Περί φυτῶν ἱστορία (“on inquiry into plants”), the same work where he talked about corals, mischaracterizing them as we have seen! Schneider has identified these descriptions of the salt-loving trees that Theophrastus places in the Red Sea with the species Avicennia officinalis, Avicennia marina or Rhizophora mucronate, the more prevalent species in that region. Additional species thrived along the Eastern Coast of Africa, especially the Lamu archipelago and further south the Rufiji Delta, where dense mangrove forests have been subjected to large-scale logging.

How were mangroves used in the ancient and medieval period? Theophrastus tells us about the medicinal use of mangrove tree and fruit sap. A little later, Agatharchides of Cnidos made the connection with the “primitive” material culture of the Ichthyophagi, who he says used these trees to construct shelters or dwellings. Clearly these authors were combining their negative valuation of cultures of the southern seas with real information about the uses of mangrove in architecture. In the period of urban expansion and port building that was ushered by the rise of the Islamic caliphates and its successor states a thousand years after the accounts of Greek and Roman authors, the dense mangrove forests of East Africa witnessed extensive logging. Muslim geographer al-Istakhri, writing in Arabic, tells us that the houses of the most important center of trade, Siraf on the Persian gulf were built with teak and “timber from the land of the Zanj;” the Zanj is an appellation used by Arabic authors for sub-Saharan East Africa, and so it’s clear, as the excavator of Siraf David Whitehouse notes, that what al-Istakhri is talking about is mangrove—in his estimation a material used for luxurious rather than primitive building construction!

In more recent times, East African mangrove timber has been harvested and exported from thick mangrove forests, such as those of the Rufiji Delta. Mangrove poles have been used in both marine and terrestrial construction. A major East African type of merchant ship, the mtepe, was often built using mangrove.

Like coral banks, which we will discuss next, mangrove forests serve as nutrient-rich habitats for an incredible variety of species. Fish, mollusks, and birds all find shelter and nourishment in mangrove mazes. These marine forests also stabilize coastlines and protect them from erosion. And like coral banks they are endangered by climate change, development, encroachment of human settlements, and overexploitation, a theme that we will return to at the end of this post.

Building with coral

As we noted in our first post on coral, the tiny and fragile coral polyps build their calcareous shell, what we perceive as coral, and in time construct a variety of solid structures including coasts and islands. In the 19th century, as naturalists began to understand the animality of corals, both scientific and other writers romantically described coral as “tiny architects,” a metaphor that Charles Darwin himself employed! Malcolm Shick, who discusses the human reception of corals as builders in his marvelous book Where Corals Lie, provides a fascinating glimpse into the social, moral, and religious messages that Victorians conveyed through their descriptions of coral polyps as industrious little builders working under God’s direction.

The structures that coral polyps built, humans living along coral shores have taken advantage of for their own building construction needs, from the islands of the Pacific to the Caribbean and the shores of Florida. The East African littoral and the Red Sea, the focus of this piece, offer excellent examples of building construction practices utilizing coral blocks.

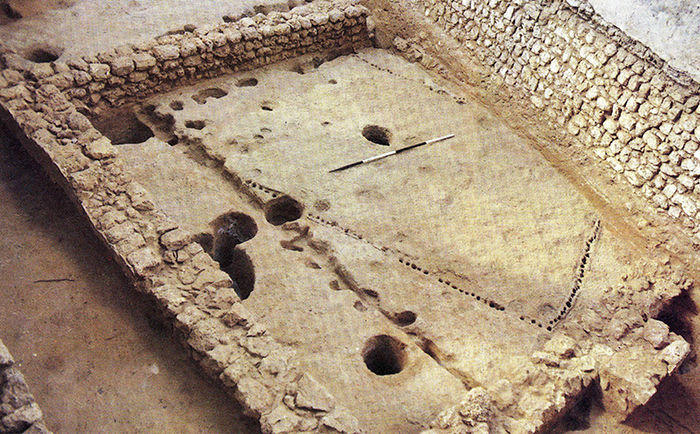

In a landmark publication of a Swahili East African archaeological site, Mark Horton described in detail the two different modes of quarrying the coral used in building construction at Shanga, an early Islamic Swahili port town in the Lamu Archipelago. A mosque at the site dates to as far back as the 8th century. From the 10th century it was rebuilt with a new building technique, one that featured blocks made of coral. In Shanga, Horton explains, coral was extracted either in its fossilized form on dry land—the term for this material is coral rag—or from the live colonies of the porites solida species in shallow coastal waters. The resulting material has different properties. Coral rag is denser more durable but harder to shape whereas blocks quarried from live coral are more maliable but also more porous. The Swahili tradition of building entire towns of this material lives on in the traditional “stone towns” in Kenya and Tanzania. “Stone” here refers to coral blocks. The Lamu archipelago and Zanzibar being the most celebrated examples of such coral-built towns.

Further north, in the Red Sea, the use of coral blocks is a basic characteristic of what scholars have called a “Red Sea style” of architecture. In addition to Suakin, the port city of Massawa offers a spectacular example of this Red Sea practice. Coral blocks make up the most distinctive feature of the town’s physical urban fabric. A palimpsest of late medieval, Ottoman, and 19th century development, Massawa has unfortunately suffered terribly during and since the Eritrean war of independence. The need for conservation is dire, but the splendor of this city built by the sea with the gifts of the sea still shines through.

Why build with coral? An obvious answer is the geology of the seaboards of the tropical and subtropical waters where this practice has taken root. In the case of the Red Sea and the East African coast, island-building coral banks fringe shores, and have, with time, become partly exposed and fossilized. While sheltering sea-life and protecting shores from erosion, these formations also result in easily accessible live and fossilized coral, quarries within easy reach.

Furthermore, coral blocks are a good material to build with. A professor of architecture writing about the conservation of the city of Suakin, Abdel Rahim Salim describes the virtues of coral blocks as “excellent” construction material thus: “Being porous, they were light in weight, had low heat conductivity, and were easy to cut.” Salim is probably referring primarily to porites or live quarried coral. Obviously the porousness of this kind of material had to be mitigated by applying lime plaster on surfaces, adding both extra labor and a particular “look” to the result. We should also add the versatility of the material. In a study of the town of Lamu in the homonymous archipelago, Usam Ghaidan describes how walls and floors were built with coral blocks set in lime mortar, while roofs were constructed with layers of coral lumps sealed with with lime plaster and set over wooden, often mangrove, beams.

How far back in time can we trace this practice? A medieval traveler whom we have encountered in previous posts, Ibn al-Mujawir testifies to the prevalence in his time, the 13th-century, of coral block construction in the Arabian Red Sea ports of Jeddah and Ghulafiqa. In his entertaining and incredibly informative travel narrative, Ibn al-Mujawir describes that the early settlers of the medieval port of Jeddah reinforced an original circuit wall with an extra layer made of hewn coral blocks and covered with stucco. In his description of the more southerly Red Sea port of Ghulafiqa in Yemen he notes that the inhabitants of that town “built fine houses and mosques with courtyards, made from kāshūr stone, which is stone extracted from the bottom of the sea.” The underwater quarrying and subsequent shaping of coral blocks that went into the construction of the medieval ports of the Red Sea thus stood out to outside observers in the past as it does today.

As Guy Standing states in his bold examination of the economy of the sea and the threats of greedy exploitation of marine resources, “reefs, seashores, beaches and estuaries are also part of the blue commons, and all are in trouble” in our days (The Blue Commons: Rescuing the Economy of the Sea, 39). The use of coral blocks and mangrove timber for land-based activities in the past does not offer a blueprint for future development because environmental conditions have changed, coastal ecosystems are degrading alarmingly fast, and development pressures create gargantuan demands that cannot be met with sustainable small-scale exploitation. Along the western seaboard of the Indian Ocean a variety of conservation efforts have focused on documentation of practices in coral block building construction, preservation of historic buildings and coral “stone towns” as in Jeddah, Suakin, Lamu, and Zanzibar, and stewardship of mangrove forests from the Red Sea to the Rufiji Delta in Mozambique. Local knowledge and collaboration with local communities are the only way to secure meaningful intangible heritage of past craftsmanship and to ensure the survival of these incredibly rich marine environments between land and sea.

Do you want to know more? We have suggestions!

Do you want to cite this work? Here is how: Margariti, R. 2025. Built from the sea: marine building materials and Indian Ocean cultures, Archives of the Sea, https://www.archivesofthesea.com/en/post/****, accessed on --****

Comments