Thynneia, tunas and an abiding story of passion and blood

- archivesofthesea

- Oct 1, 2025

- 22 min read

Updated: 4 days ago

By Dimitra Mylona

The many names of a tuna trap: Θυννείο, Θυννί, Al-mādhraba Madrague,

Tonnara, Almadraba

It was the end of a bright and warm April and the sea along the western coast of Attica had been calm for days. At the deme of Halai Aixonidae, near what later became Vouliagmeni, as elsewhere in the Saronic Gulf, excitement and apprehension kept fishers awake at night. The tuna fishing season was about to start. But would tunas show up this year? Would they come close to the shore and fall in the trap already deployed for them? It took days to secure the sturdy nets, the wooden poles and the stone anchors in the sea and to set up the thynneion, the large stationary tuna trap they were so proud of. The σκοπιορός (guard, lookout) was already perched on the watch tower, praying and waiting for the signs: some gleaming on the surface of the sea, a sudden darkening of the water, some local disturbance and sea birds gathering around, and that deep feeling of something momentous about to happen! All these would tell him that the tunas had arrived and that it was time for him to shout the news and for the thynneion crew the act; time for the battle with the swarms of fish that the sea kept bringing them every year to begin.

Not one, not two, not even a dozen, but hundreds of large tunas were caught every year here and in so many other spots along the coast! The fish markets in the nearby villages, and even the voracious fish market of Athens, were overflowing with tuna meat at this time of the year. Fish peddlers brought the magnificent fish to villages and hamlets in landlocked places or even on the mountains. Inscriptions from the 5th century document that fish peddlers carried fish on foot as far as 60 km away from the sea to sell. What could not be consumed fresh, fed the insatiable fish salting business. Tuna fillets, dry salted or cured in brine, trigona (of triangular shape), tetragona (or rectangular shape), and many other types would go around the market, the humble kitchens of town houses and the sympotic tables of the rich for months to come, reminding everyone that tunas were a true blessing!

But at Halae Aixonidae, on this warm April day, the stakes were high. It was not just the uncertainty of the outcome of the tuna fishing season, it was not just a matter of an empty or a full pantry for the fishermen’s families, it was also the important matter of the tuna festival! At Halae Aixonida, fishers, and pretty much everyone else, knew that in order for the sea to bring them the tunas that ensured their well being Poseidon had to look favorably upon them. Every year, when the tunas approached the coast on their seasonal rounds, a festival was held, the Thynnaion, to honor Poseidon, the lord of the sea, to show him reverence and offer him a share of the catch. The “first fruits” of the tuna fishing season were his!

But would the tunas appear this year? Will the community be happy and the god receive his honors? Or would the tunas stay out at the sea, and people’s efforts and preparations be all in vain?

This snapshot of a spring day on the Attic coast, sometime in the Hellenistic period (end of 4th- middle of 1nd c. BCE) is not fictional. It is based on historical and archaeological evidence, with just a little bit of poetic license thrown in. It was repeating itself for centuries on the coasts of the Mediterranean, east and west with small variations. Tuna fishing, seasonal, capricious, violent and prolific, shaped people’s perception of the marine world, created wealth, promoted industrial growth and opened a wide trade network all over Mediterranean and across the world of the time.

Tunas… what’s in a name, what’s in a fish

Tuna is a word that, like others in marine life, is not exact at all! It does not refer to a specific species of fish but sometimes we use it to speak casually about the large blue fin tuna. Some other times we use it to refer to two or three species of fish that share some common features: they are large bodied, they are seasonal and they all belong to the Scombridae family. If we want to be exact, the large tunas, the blue fin tuna which is the star of this post, is formally called Thunnus thynnus.

The Latin double names that are used in science, following a taxonomic system devised by Linneus (mentioned in a previous post on corals), create, in people’s minds, some kind of order in the chaotic natural world. The name Thunnus thynnus tells us that we are dealing with a creature that belongs to the genus Thunnus (same as Roxani’s surname is Margariti and mine is Mylona) and to the species thynnus (same as I am Dimitra and my co-bloger is Roxani). In this taxonomic scheme there is only one type of fish that can be called Thunnus thynnus (although I am sure there are more than one Roxani Margariti and Dimitra Mylona in the world). There are other fish that belong to the same genus Thunnus, but they have a different species name: Thunnus alalunga (albacore), Thunnus albacores (yellow fin), Thunnus obesus (bigeye ) and others. The creatures that share the same genus name are the closest in the taxonomic tree, they are more closely related. The Scombridae family however has more genera in it with a variety of names. Such taxonomies are built on the basis of morphological characteristic, such as, the number and type of fins rakes, the number and shape of color bands on the body, etc. In the world of scientific taxonomy, things appear orderly.

In the world of fisheries, however, especially the pre-modern type, categories become more slippery and the taxonomic criteria are more fluid, changing over time and space, and adapting to local interests and practices. For instance, ichthyologist D. Papanastasiou (in Alieumata, Athens 1976, pp. 502-3) informs us that in the Turkish market of the early 20th century pelamids (Katsuwonus pelamis and Sarda sarda), two different species, are grouped together and are known with different shared names depending on their weight. Palamut: 0.5-1 kg; bonito: 2-4.5 kg; torik: 4.5-7 kg; lakerdit: over 7 kg. Here it is not the actual biological identity that is important but a market-related feature.

Modern ethnography and anthropology have developed a term for the phenomenon: these are folk taxonomies, which are build around the cultural interests (economic, ideological, political, etc) a community has for the particular type of organism. For most lowland Cretans for example, the word snow covers three different things: snow, sleet and hail. That is only natural. For most of the island of Crete snow is a rather rare phenomenon, little understood. On the same island, however, there are very many words to describe the sheep and goats, depending on their age, sex, stature, coloring, shape of horns, color of eyes, special individual features etc. Sheep and goats are culturally very important. People need more categories to describe them. Similarly, in Istanbul of the old days the migratory pelamids and bonitos were also important enough to merit the creation of a special terminology.

For those of us who study the lifeways of people of the past, this realization is fascinating! It makes sense… but it also creates serious problems. The ancient and pre-modern discourse on tunas exemplifies this splendidly. When we read ancient or more recent texts on tunas and other members of the Scombridae family or when we read about their capture, we have the constant feeling that exactness is elusive… we can fully understand the meaning of the texts, but we are still unable to speak about the topic in exact, unequivocal terms that modern science requires. In this post we will try to sort things out, but we will not delve deep into the problem. Check out the bibliography at the end of the post for this.

The Scombridae as a group are found all over the world’s oceans and constitute a discrete family even though they may range enormously in size, from the relatively small mackerels which may reach a maximum length of 66 cm but are usually around 30 cm long, to the blue fin tuna that can reach enormous sizes (e.g. 680 kg) but can easily be 200 kg and 2 meters long. They share certain common features. They have a hydrodynamic shape that facilitates swift swimming, they have fatty flesh and they are gifted with a very efficient circulatory system. They are pelagic, forming large, and sometimes enormous, schools and their life is governed by the almighty instinct of reproduction.

Blue fin tuna: biology moves the hands of the fishers

For centuries, naturalists, philosophers and biologists that lived around the Mediterranean were pondering over several tuna mysteries. Where did blue fin tunas come from? Where did they go after they bred? Why had no one ever seen their young? Why were certain seas, such as the Sicilian waters and Sea of Marmara so much richer in tunas than others? Several theories were put forth, some imaginative, other surprisingly accurate despite their early date. Modern marine biology and oceanography solved (most of) the mysteries. Blue fin tunas, because of their economic importance, both in the past and now (see for instance the significance of the globalised craze for sushi), are on the verge of population collapse, and their numbers have dramatically decreased almost everywhere in the world. In 1966 the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICAAT) was established dedicated to the conservation of blue fin tunas and related species in the Atlantic and adjacent seas. This initiative and a general concern for tuna fisheries and ocean conservation led to a blooming of research on “all things tuna”.

Tunas are cosmopolitan fish and they swim in all warm and temperate oceans of the world, with the exception of the cold regions of north and south. They have a life span of more than 30 years and they can reach enormous sizes. They are pelagic fish that can dive as deep as 1000 m or deeper. They form large schools of several hundred or even thousands individuals each, and they travel huge distances during their migration. It was suspected for centuries—and modern tagging programs have proved it—that the Atlantic and Mediterranean tuna populations are intermixed to some degree with individuals moving in and out of the Gibraltar straits. Others prefer to stay on either side of the straits, some moving along the whole Mediterranean and some forming even more local populations.

During their yearly migration they move, from their feeding grounds to reproduction grounds and back again, creating a pattern of movement, which, albeit sensitive to environmental conditions such as water temperature, ocean currents, etc, is extremely persistent. Timing, routes and scale of migration vary from year to year, and from one geographical region to the other, and it is species-specific, but the fact that it happens almost every year without fail, has been a key factor to the exploitation of blue fin tunas and other Scombridae by fishers all over the world for millennia.

Fishers have observed these patterns and the fishes’ behavior, they understood the repetitiveness of their movement and came to expect their arrival. They created technology that takes advantage of the Scombridae biology and behavior and they built wealth and culture based on them.

Wherever the scombrids appear, fishers expect to also find other types of marine creatures: small pelagic fish that are pray to the scombrids, such as anchovies, sardines etc. and larger predators that feed on them, such as sharks, whales, sea turtles etc.

The world of tunas and other scombrids is a complex and well populated one.

Blue fin tunas’ yearly life circle has two distinct phases. When the fish reach sexual maturity (about 3-5 years of age and 80-100 cm in length) and every year for the rest of their lives, embark on a reproduction journey that brings them thousands of kilometers away from their feeding grounds. They move towards waters warmer than 20ᵒ C and with the increasing temperatures on their way, their spawn matures and becomes ready. There are certain areas that are considered optimal breeding grounds where, in the past, vast numbers of tunas used to congregate every year to reproduce. The females spread their spawn, millions of tiny shell-less eggs, just 1 mm in diameter, to be fertilized by sperm also spread by male fish. The eggs and the larvae that hutch from them (larvae are active, immature form of fish and other organisms, e.g. insects) are buoyant and float just under the surface, offering a bonanza of food to very many sea creatures. In the Mediterranean Sea tunas congregate to reproduce at the Balearic Islands, Malta, Aeolian Islands, in the Levantine Sea, including the Aegean. In older days tunas were also entering the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea but extreme pollution and marine traffic of the last decades keep them away.

After reproduction is concluded, the fish return, lean and exhausted, to their feeding grounds, oceanic expanses of high productivity, where they remain for months to replenish their reserves and grow, preparing for the next mating season. Even with the current diminished population of blue fin tunas, their reproduction gatherings are truly impressive.

Blue fin tunas move in predictable patterns, anti-clock-wise, along the coast to reach their spawning grounds (reproductive migration), and on their return (feeding migration). Pliny, in his work Natural History in the 1st c. AD claimed that tuans adopted this consistent direction of travelling because they could only see with their right eye, the strongest one (HN IΧ, 18, 47, 19, 49). On their reproductive journey they tend to form large tight schools that swim very near the coast, entering coves and sandy bays, in search of warm calm waters. During this phase they do not eat, thus angling is not possible. On their return trip they stay more off shore, in looser formations and they feed on the go.

An implication of the above, very important in terms of archaeology and economic history, is that even though blue fin tunas are pelagic fish, they can actually be caught very near the coast with fishing technologies used for inshore fishing! A second implication is that the shore based stationary traps mostly target fish on their spawning migrations, because they come closer to the shore, within the reach of the tuna traps. The fish on their return trip form more dispersed schools that at that stage can take the bait so, in theory, they can be caught by other means, such as hooks and lines. Finally, this look into tunas physiology and habits makes it clear that when they arrive in schools, fishers can end up with a huge amount of fish flesh per fishing effort! In older times when refrigeration was not an option, and transportation to large markets was inefficient and time consuming, a bonanza of tuna meat demanded conservation solutions…. The meat had to be preserved or it would be spoiled and lost!

Ιn this post the issue of tuna flesh preservation will be just a side note. We have already discussed some aspects of it in our post on garum. What follows focuses on the way tunas were caught in the Mediterranean in the past and particularly in the iconic thynneia, the stationary tuna traps!

Blue fin tuna: how to catch them.

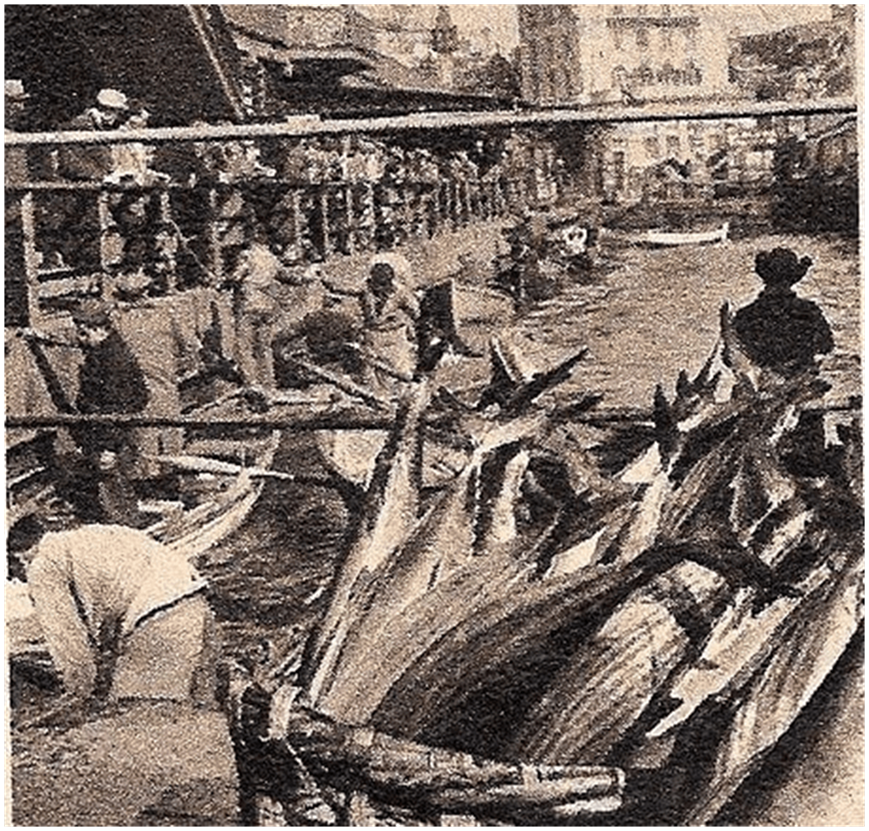

One cannot talk about the thynneion without also discussing its elemental version, the circling net or beach seine. Its working is simple and its efficacy is proved over the millennia being a basic tool used in ordinary small scale inshore fishing. When tunas enter a cove, or approach the beach, fishers, who anticipate their arrival, watch for it and are prepared. They use a boat to deploy a long net from the coastline out to the sea and back again to the coast, encircling a section of the school. A group of fishers on the coast start pulling the net in, in the same manner they do with the beach seines, gradually reducing the space available to fish, until they are all entrapped in the shallows, surrounded by the net and unable to escape. At this stage fishers attack the fish with clubs, hooks, and tridents, killing them. They then bring the large, silvery, and very bloody bodies on land. Capture of tuna fish by beach seine was not restricted to antiquity and the early stages of this activity but was used even in the high days of tuna fishing and processing in the 19th and early 20th centuries, as seen in the last of the following images.

A thynneion is a more complex version of the same thing. But instead of the movable beach seine which is deployed only when the tuna schools are spotted, the thynneion is set up once every year and stays in the water for months, until the end of the tuna fishing season. It is a stationary device.

The drawings above show clearly the basic components of a stationary tuna trap large and small. Several pieces of net are set upright in the water with the help of wooden poles several meters high that are driven into the sea bed and kept in place with an arrangement of ropes and stone or iron anchors. This combination of nets, poles and anchors creates a barrier that extends several meters (even hundreds of meters) into the sea, forming, in its more elaborate versions, a system of passages and “rooms” or in its simplest form just a barrier and an enclosed space. This type of trap, which Oppian, in his 2nd c. AD poem Halieutics (III, 633-642) described as a city of nets with gates and guards and recesses and passages, is met by the migrating schools of tuna that are moving along the coast in the relatively shallow, warm waters of bays and coves, on their way to reach their spawning grounds. Because tunas cannot turn back to exit the narrow spaces created by the nets, once they hit the first obstacle, they keep swimming along it, thus moving deeper into the trap. The fishers who work the thynneion are present, on small boats, constantly re-arranging the partitions of the trap, lifting nets to seal the bottom, dropping nets to shut the doors and enclose the tuna schools in increasingly narrower spaces. The fish ultimately reach the death chamber, the dreadful inner space of the trap where the tunas, frightened, desperate to escape, and frantically thrashing around, meet their death. Fishers club them, hook them, and pull them out of the water that, by that time, has turned bloody and frothy from the battle that takes place in it. The bodies are moved onto the boats, to be taken out of the sea, to the beach. There, they either take the route to the market or to the fish processing workshop.

An integral, crucial, part of a thynneion is the skopia, the watch tower. A skopia could be a high spot on the shore, the tip of a promontory, or any other physical point in coastal topography that would offer a clear view of the sea. Oppian describes it quite eloquently: there (at the location of the thynneion)a skillful tunny-watcher ascends a steep high hill, who remarks the various shoals, their kind and size and informs his comrades” (Op. Hal. III, 637-640, English translation by A.W. Mair, 1963).

Where such features were not available, man-made wooden towers were erected by one or more long, intersecting wooden poles that were crowned with a small platform on top where the skopioros, the watchman, stood. The watchman was a very important member of the crew with excellent eyesight and deep knowledge of the signs of the approaching fish schools. How many fish were approaching and from what direction exactly, of what kind, what size, etc., was information that he relayed to the thynneion crew, in order for them to make the necessary moves. In ancient Greek literature the term thynnoskopos (watchman for tunas), became a literary topos, a commonplace theme, used to describe the excellent ability to spot differences. Apparently people did not need an explanation of what a thynnnoskopos was. A number of inscriptions from Hellenistic Greece highlight the importance of the watch towers. When thynneia were rented out by sanctuaries or poleis to individuals, there was always reference to the watch tower as central element of the property.

The stationary tuna trap is a seasonally used tool. When the tunas go away, the thynneion is disassembled and its elements are stored. So, every thynneion is linked to some storage buildings on the shore. On the fabled Favigniana, one of the Aeolian islands, where the last of the Mediterranean thynneia is still barely surviving (there they are called tonnarae) the storage buildings are like cathedrals, with high openings shedding light into the cavernous interior. The tonnaras of Favigniana were very large and very productive during the past few centuries and the volume of the stored nets, wooden poles and boats was massive, representing considerable part of their owner’s wealth and power.

These basic principles in the workings of the stationary tuna trap, whether small and rudimentary or large and elaborate, ancient or contemporary, in the Eastern Mediterranean or in the west, did not change much over time. Innovations were certainly introduced, but their timing is not always clear. Throughout the history of the thynneion use in the Mediterranean, there were periods of expansion and flourishing that are clearly seen in the historical/archaeological record. At other times we barely find even indirect evidence for their use. The tuna traps that are known today and in the last few centuries, reflect a pan-Mediterranean shared tradition. A word related to the operation of a thynneion beautifully illustrates this issue: The term for the head of a thynneion is an Arabic word, Reis (or ra’is in proper transliteration), the chief or captain! This was adopted by the Spanish, French and Italians in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and at some point by the Turks and Greeks in the sea of Marmara. Certainly, knowledge, tradition and common practices were circulating along with people and ideas in the marine realm of the Mediterranean.

A thynneion encompassed what Spanish archaeologist Dario Bernal Casasola calls “The Halieutic Circle”, e.g. a number of integrated activities that all stem and supported from this type of fishing: capture of the fish, processing of its flesh, trading and consumption of the final products, creation of gastronomy and wealth.

The topic of the stationary tuna traps is certainly not covered by this short post. Much more can be said about the people who manned the traps (all male), the history of the tool, its political implications in the lives of fishers and whole countries. If your curiosity is picked however, have a look at our bibliography.

Do you want to know more? We have suggestions.

If you want to cite this paper:

Mylona D., 2025. "Thynneia, tunas and an abiding story of passion and blood", Archives of the Sea, https://www.archivesofthesea.com/en/post/thynneia-tunas-and-an-abiding-story-of-passion-and-blood , acceced on **-**-****

Comments